College papers come in all shapes and sizes. And different assignments will require different strategies. If you're working on a research paper — a paper that involves citations from books, articles, and Web sites — then the guidelines in Section One will apply to you.

College papers come in all shapes and sizes. And different assignments will require different strategies. If you're working on a research paper — a paper that involves citations from books, articles, and Web sites — then the guidelines in Section One will apply to you.

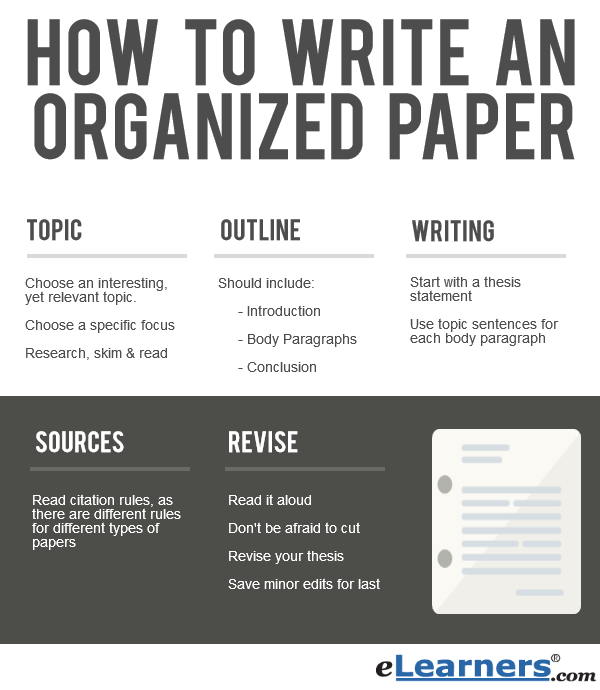

Section One: Your Research Paper Topic

Choose an Interesting, Yet Relevant Topic

When choosing a research paper topic, it's a good idea to think about the issues and questions that interest you. You're going to do a lot of reading on this topic, so you might as well read about something you enjoy. At the same time, it's a good idea to get your paper topic approved by your instructor. Even if he or she doesn't require this step, you'll be glad that you checked. Instructors assign papers to compliment the lessons they are teaching. If your topic is too wacky, too abstract, or too unrelated, it might affect your grade.

Choose a Specific Focus

Once you have a topic in mind, you need to determine how you'll approach the information. Let's say you've decided to write about the American Civil War. Now you need a focus.Are you going to focus on the root causes of the Civil War? Will you write about specific battles? Or are you most interested in women's contributions to the war efforts?

As you're considering your focus, you should keep 2 things in mind. Firstly, what is the assignment due date? Secondly, what is the recommended length?

Some students assume that writing more is always better, but many professors don't want to read a 15-page paper when they've only asked you for 3 pages. Also, if the paper is due next week, you need to be realistic about the amount of material you can cover. More often than not, it's better to err on the side of a very specific topic. If your focus is too broad, your paper will wind up sounding like a superficial overview of information that most people already know.

Research, Skim, and Read

Before you start writing, you'll need to get acquainted with your topic and your focus. Even if you're already quite knowledgeable about a subject, it's useful to read other people's theories and opinions. The reasons why you agree or disagree with them will help you to sculpt your own point of view.

Take an afternoon to skim several different sources. Skimming is not like close reading. You don't need to absorb every word; you just need to determine what's relevant. Create a "yes" pile and a "no" pile for the documents you skim. You'll return to the "yes" pile, and reread those items closely.

Reliable Web sites are a good source for data gathering. Sometimes it's difficult to differentiate between reliable online sources and unfounded online sources. But there are some basic tips. For example: never trust an article that doesn't mention its author's name. And focus on information that comes from government or university Web sites; these URLs should end in .edu or .gov. If you're still confused, most librarians — either at your local library or via your school's online library — can help you search academic journals and articles.

This is also a good time to determine whether or not there are enough resources available to inform your paper. Here again, if your topic is wacky or abstract, you may not find enough data to support your ideas. If your paper assignment calls for a specific number of sources, make sure you have them in hand before you start writing.

You should also start taking notes. Don't worry about writing in full sentences at this point. Just jot down main ideas, and highlight the areas of text that seem useful. As you're reading about Civil War nurses for example, you might come across major terms and names: the Sanitary Commission, Clara Barton, Document Number 19, etc. These subjects may wind up as paragraphs in your paper, or they may not fit into the final draft. Either way, your preliminary research will help you shape your ideas.

Section Two: Your Paper Outline

For some reason, students hate outlines. Maybe an outline seems like a waste of effort, since you won't get any credit for creating one. Maybe an outline looks too complicated. Maybe you're already crunched for time.

But starting a written assignment without a plan is like building a house without any blueprints. You'll end up with pieces that don't fit together, and you'll probably run out of materials. Drafting an outline before you start writing will help to ensure 3 things: 1.) your paper will be focused, 2.) your ideas will flow naturally from one point to the next, 3.) you won't waste time writing paragraphs that you can't use in the final draft.

Your paper outline should include 3 main sections: an introduction, a group of body paragraphs, and a conclusion. You can map these elements on paper, like so:

- Introduction (including thesis statement)

- Body Paragraph 1

- Body Paragraph 2

- Body Paragraph 3

- Conclusion

Here's an example of how an outline might represent the ideas for an actual assignment:

- Introduction (thesis: Women played many important roles during the American Civil War.)

- Body Paragraph 1: Women supported the troops from home.

- Body Paragraph 2: Women acted as nurses for wounded soldiers.

- Body Paragraph 3: Some women impacted battles.

- Conclusion (History might have been different without these contributions.)

If you're not an expert at outlines, don't worry. No one will see the outline except for you, so it doesn't matter if you use a perfect format. The most important thing is that your outline gives you a clear picture of which ideas your paper will address.

For longer papers, you'll need to include more than just 5 paragraphs in your outline. Longer papers require you to develop ideas even further. You'll need to find ways to build on your main paragraphs, with supporting paragraphs.

One way to build on a main paragraph is to ask the questions "how?" or "why?" Here's an example of how we built on the above outline, by asking "how?" or "why?" after each main idea.

- Introduction (thesis: Women played several important roles during the American Civil War.)

- Women supported the troops from home. How?

- Women supported troops from home by organizing aid societies.

- Women supported troops from home by taking over male household roles.

- Women supported troops from home by circulating petitions and writing letters.

- Women acted as nurses for wounded soldiers. How?

- Dorothea Dix recruited women to serve as nurses in the Army Medical Bureau.

- Clara Barton cared for returning soldiers and men on the front lines.

- Nurses also monitored patient diets, cleaned infirmaries, managed linens and supplies.

- Some women impacted battles. How?

- They disguised themselves as men and fought alongside male soldiers.

- Some women acted as spies.

- Conclusion (History might have been different without these contributions.)

Just like that, your 5-paragraph paper is now is 13-paragraph paper. And if you needed to, you could dig into these areas even further.

As you become a better writer, you'll start to outline your ideas automatically. You'll get better at determining which ideas are worth exploring and which ideas are not. You'll also find that it's easier to choose a topic and start your research, when you're good at envisioning how levels of information can fit together.

Section Three: Start Writing!

Introduction Paragraph with a Thesis Statement

An introduction is the first paragraph of any academic paper. If the paper is particularly long, the introduction might span 2 or 3 paragraphs, but sticking to 1 paragraph is a good rule of thumb. As its name would suggest, an introductory paragraph introduces the ideas that your paper will discuss. The introduction might also offer a bit of context, very much like a movie prologue, which prepares you for what's about to happen.

At the end of your introduction, you should include a sentence that specifically states the point of your paper. In other words, why are you writing this? What is your paper going to teach the reader? This sentence is called a thesis statement.

If you're having trouble coming up with a thesis statement, you might need to rework your outline. Or, you might need to read a bit more about your subject. When it comes to academic writing, writer's block is almost always caused by a lack of information. If you don't understand your topic, you won't be able to discuss it in your own words.

That doesn't mean that your thesis statement needs to be complex. In fact, beginners may find that it's easiest to follow a simple formula when crafting a thesis statement. Use your topic to fill in the following blanks:

[Noun] + [verb] "because" [3 or more reasons].

Here's an example of how a contemporary paper topic might fit into this thesis formula:

Universal healthcare [noun] would improve [verb] Americans' health because everyone would receive medical coverage, prescriptions would be less expensive, and preexisting conditions would not be an issue [3 reasons].

Write Your Body Paragraphs

The body of your paper includes all the writing that goes in between your introduction and your conclusion. In a short paper, also known as a 5-paragraph essay, you would only have 3 body paragraphs. In a longer paper, you might have 15 or 25.

The most important thing to keep in mind with body paragraphs is proportion. If you're addressing 3 different ideas in your paper (like the healthcare facts mentioned above), you shouldn't spend 12 paragraphs talking about the first idea, and only 1 paragraph talking about the other 2 ideas. If you do this, your paper will appear lop-sided and incomplete.

Use Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph should have its own focus. One way to ensure focus in your paragraphs is to begin each one with a topic sentence. A topic sentence is like a mini thesis statement. Your thesis explains why you're writing the paper, and your topic sentences explain why you're writing the paragraphs that go into your paper. Without a topic sentence, your reader might be left wondering: why is the paragraph necessary? Or, how does this relate to the overall point? If you did a good job crafting your outline, your topic sentences can be taken directly from that list of body paragraphs.

Section Four: Cite Your Sources

If you are using information from other writers and researchers, you need to cite your sources. This is true even if you don't use the other person's exact words. If you've never had to cite sources for a paper, you should probably contact a tutor from your school's online writing center. Or, borrow a library book that outlines academic citation rules. Citations aren't difficult, once you understand when and how to incorporate them.

You should also note that rules for citing sources differ, according to the type of paper you are writing. Psychology papers, sociology papers, and education papers usually follow APA (American Psychological Association) citation guidelines. Papers about literature or the arts usually follow MLA (Modern Language Association) guidelines. Most instructors will clearly state which set of rules you should follow. If he or she doesn't, make sure that you ask.

For more information on direct quotes, paraphrasing, and citation strategies, read How to Avoid Plagiarism.

Section Five: Revise

Finally, you will finish writing — at least temporarily. Before you hand in your completed paper, you'll want to test it on an unbiased reader. Here are some strategies for optimizing your revision process:

Read Aloud

When you revise a paper, you need to do more than just spell check. Read your paper aloud. You'll be more likely to catch errors or awkward sentence construction if you can hear the way your words sound. You should also ask a friend or classmate to read your paper. Your ideas are bound to seem clear to you because you've been working with them for several days. However, someone who is new to the material can quickly point out any areas that are confusing or rushed.

Don't Be Afraid to Cut

Some students fall in love with their own writing — even if it's garbled or dense. But remember that good, academic writing doesn't have to be complex. Your instructor will be far more impressed with clear and orderly writing than with big words and mile-long sentences. If you discover that some of your paragraphs sound confusing, try to rewrite those sections. You may have to cut out those paragraphs entirely. It's frustrating to delete your own sentences, but your paper grade will benefit from your ability to prioritize.

Revise Your Thesis (if Necessary)

You may discover that much of what you've written doesn't support your original idea. Or maybe the bulk of your paper focuses on just one aspect of your original thesis. Don't worry. Simply rewrite your thesis to fit the angle of your content. Make sure the introduction and conclusion also coincide with your new aim.

Save the Minor Edits for Last

Don't worry about commas and spelling until everything else is in place. If you're fretting over every punctuation mark, you'll never get to address the larger issues — like content and organization. It's true that instructors grade your paper with an eye for typos and grammar mistakes. But they are much more concerned with the substance of your paper.